The Gang of Four

By Larry Gossett, ’63

The "Gang of Four" were Larry Gossett,’63, Roberto Maestas, Bob Santos, ‘52, and Bernie Whitebear. It began in the heat of battle within the walls of Franklin High School on the afternoon of March 29, 1968. Early in the afternoon, more than 100 Black students at Franklin took over the principal’s office in a classic, student protest sit-in. They said they were not leaving Principal Loren Ralph's office until their five demands were met.

Many people questioned how this could happen—way up in the “peaceful, quiet, Pacific Northwest city of Seattle.” Many also said: “There is no racial tension up here.” King County Prosecutor Charles O. Carroll said on the news of a local TV station on April 2nd, that the "only way our Negro students would allow themselves to risk their freedom like this, is that some radical Black Power activist, from outside of Seattle came up here and made them think they were being discriminated against.” Mr. Carroll finished his statement emphatically stating: "We are going to find and arrest these troublemakers from outside Seattle."

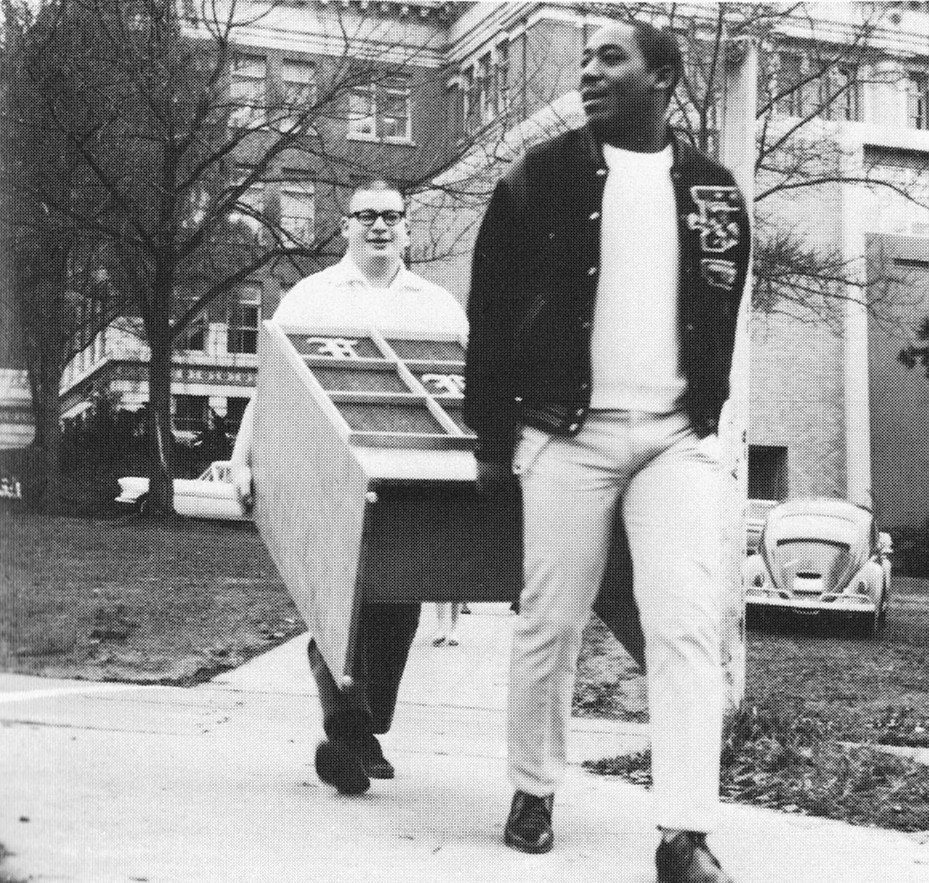

Gang of four: Bob Santos, Bernie Whitebear, Larry Gossett, Roberto Maestas.

Photo courtesy UIATF

The heart of what happened at Franklin High School that day gave rise to the formation of the Gang of Four. On March 29, 1968, at about ten a.m., Larry Tukes, a student at Franklin, called the University of Washington Black Student Union office, and I answered the phone. He immediately started screaming, "We have had enough, brother Gossett, of the racist disrespect we been getting all year from the white principal and vice principal here at our school. Brother Gossett," I was told, "we gonna burn Franklin to the ground! We are tired of all of this racial prejudice.”

I quickly stopped him and said, "Hold on, why are you talking like this?” I told him that I would bring some Black Student Union (BSU) brothers with me, and we would come down to Franklin, “right now, and help y'all organize.” But – “Do not do anything; rally all the Black students you can, and tell them to meet us across the street from your school building, in front of the Beanery.” I knew we did not have much time, so I just asked the guys in the BSU office to ride down to Franklin with me. I told them there was serious trouble brewing. I told the cats,

“We gotta go now.” Those accompanying me were Aaron Dixon, Eddie Demings, and Carl Miller.

Photo from Gang of Four: Four Leaders, Four Communities, One Friendship.

By Bob Santos and Gary Iwamoto. 2015

When we were just a couple blocks from Franklin, we saw dozens of police cars gathering in Seattle Rainiers Sicks Stadium ballpark. We knew they were going to arrest our sisters and brothers at Franklin, so we hurried up, turned onto South McClellan Street and zoomed to the Beanery—the eatery across the street from Franklin. We were happy to see all the Black students waiting for us. We quickly parked our car and hurried up and joined them. They were happy to see us.

I said, “We think you should decide what we are going to do to bring some Black Power to Franklin, what changes you want to see at Franklin, what your demands are.” One of the students said, "We need to take over the school and have a sit-in in the principal’s office.” We heard a lot of agreement with this plan, so we urged them to take a vote and then quickly develop the demands for changes that would benefit Black students. They had a senior who had brought her notebook write down the demands and reforms they wanted to see implemented at Franklin:

Do not suspend or expel the two Black students who earlier that day had fights with white students. Both of the white students were sent back to class and the two young Black students were told they were kicked out of school. They were Charles Oliver and Trolice Flavors, both of whom had represented Franklin at citywide BSU meetings. (I was chair of the Seattle Alliance of BSUs on Sundays.)

Do not suspend the two Black girls who had already had notes sent to their parents saying they would face suspension if they did not stop wearing a natural hairstyle to school. The vice principal’s note to their parents said, “Your daughter must look ‘ladylike’ to remain in Franklin.” In other words, they must return to “straightening their hair.” These girls were both seniors: Nan Williamson and Joyce Driggers.

Franklin must hire a Black principal. There had not been one at the high school level in the hundred-year history of public high schools in Seattle.

Franklin must employ, the first ever full-time Black-history teacher. None had ever been hired at any school in the city.

Recognize the BSU as an official student group and allow it to put up posters that represent Black heroes, like Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X.

Roberto Maestas at a City Council hearing, Seattle, November 10, 1972

Photo credit:MOHAI, Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, 2000.107.117.04.06, photo by Tom Barlet

Principal Loren Ralph and Superintendent of Schools Forbes Bottomly both accepted these demands. Neither had ever had a challenge to their plantation-style operation of their campuses before.

After getting a concurrence on the demands, the students went to the auditorium to vote on accepting the principal and superintendent’s positive responses. On the way there I saw who I thought was a white adult in the hall mingling with the Black students. I asked the students, “Who is that white man y'all talking to?” They said, “Brother Gossett, that is not a white man, he is Mexican and he is our Spanish teacher.” I said, “I want to meet him,” and two of the students took me over to meet him: " Mr. Gossett, this is Mr. Roberto Maestas, our Spanish teacher, and he is cool." Roberto later told me he was extremely proud of how articulate the students were in the auditorium in explaining their demands, and he was impressed by how united they were. He called the afternoon "awe inspiring!"

Bob Santos, photo credit Joe Mabel (Wikipedia)

"Mr. Gossett,” another Franklin staffer later said to me, "our Black students were really woke, aware of what had been really happening to them." Later some of the students said that the next day, Mr. Maestas went into the teachers’ lounge in the morning and told the ten teachers lounging in there, "Hey, you all, listen up, I will from this day forward not answer you if you call me ‘Robert’ or ‘Bob,’ I will only respond to ‘Roberto!’"

Roberto and I became especially close comrades in the years that followed. I met Bob Santos first, and then later Roberto met him. All of us were part of community organizations that needed meeting spaces on a regular basis, and we wanted to meet in the Central Area. In the fall of 1968, I told Bob that I needed a place to meet every Sunday for the Seattle Alliance of BSUs meeting, and we had not been able to find a reliable place because people are scared of our militancy. Bob said we could all use a classroom on Sundays at the St. Peter Claver Center on 19th and East Jefferson Street. (Now the Brooklyn Waldorf School). We were happy to hear him say that. Then I said in a stuttering voice, "How much... How much... is the rent?” Mr. Santos said, "Do not worry, the lord will make a way." The Seattle Alliance of BSUs met there for fourteen months and Roberto's English as a Second Language (ESL) program was there for nearly two years. Roberto, Bob, and I started comparing notes on community struggles and discussing how we could provide mutual aid and support at St. Peter Claver Center.

Bernie Whitebear (1971). Photo credit: Cary Tolman, MOHAI.

Roberto told me one day in the early summer of 1969 that a native leader by the name of Bernie Whitebear, whom he had met the year before at Alcatraz when Indian activists took the prison over as a piece of land owned and promised to local native tribes, had called him and asked whether he could get some other non-white activists to come down to Frank's Landing, to join native activists trying to protect their historic right to fish for salmon on the Puyallup River. Bernie was from the Colville Tribe in Eastern Washington. I had just been elected the new president of the BSU at the UW, and I gathered several of our members and went down to Frank's Landing.

Frank's Landing was the first great struggle the "Gang of Four" worked together as a team. From that beginning we became comrades, friends, colleagues, and brothers. That will not change even when I pass, because when I go to "the happy hunting grounds,” (as Bernie would call it), I am confident that our spirit will live on in many of the younger brothers and sisters who learned about united front fighting from us.

Returning to the beginning, March of 1968, the senior prosecutor Norm Mailings rounded up and charged with “unlawful assembly,” all of the following: Larry Gossett, Ricky Gossett, Aaron Dixon, Carl Miller, and Trolice Flavors all charged as adults; taken to juvenile court were Charles Oliver, Elmer Dixon, Clifton Wyatt, and Larry Tukes. Mailings confidently predicted that organized agitators from “out of town” would be found guilty of getting more than 100 Black students to sponsor the takeover of Franklin's principal's office. Aaron Dixon, Carl Miller, and I were found guilty of a gross misdemeanor and sentenced to six months in the county jail and fined $1,500 each. At the time we were all University of Washington students in good standing with no previous criminal record.

Seven of the young Black males listed above went to kindergarten through twelfth grade in the Seattle Public Schools. Five of us were born in Seattle, Washington, including myself.

We came together to struggle for civil and human rights in each of our respective Seattle neighborhoods. We worked on and provided support for one another on many community projects between March 1968 until the end of 2010 (forty-eight years). We were all very strong and determined leaders.

Now, were we outside agitators coming from out of town to "upset young, impressionable, Negro students?" No, we were all homegrown, intelligent men of color, able to notice racism when we saw it.

Larry Gossett, ’63

Larry Gossett speaking at anti-stadium demonstration, Seattle, February 3, 1975

Photo Credit: MOHAI, Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, 2000.107.077.01.05, photo by Tom Brownell.

Editor’s Note: The Gang of Four was also known as the ‘Four Amigos.’ Mr. Gossett is the last amigo standing. He is a native Seattleite. His parents came from Texas in 1944. Roberto Maestas (1938 -2010) graduated from Cleveland High School (‘54) and the University of Washington, (‘65), and immediately was hired to teach Spanish at Franklin High School. He was first generation: his parents were Mexican. Bernie Whitebear (1937 - 2000) was officially Chief White Grizzly Bear of the Lakes tribe. His father was first generation Filipino, and his mother was the daughter of the chief of the Lakes tribe. Bob Santos, (1934 - 2016), ‘52, wrote a history of the Gang of Four, and died the year following its publication. He was first generation Filipino.

To read more: The Gang of Four: Four Leaders, Four Communities, One Friendship, Bob Santos and Gary Iwamoto, 2015. Publication made possible through the generous support of the Muckleshoot IndianTribe,Auburn, WA.

Gang of Four book cover, 2015 Chin Music Press.