Rainier Valley’s Demographic Odyssey

Submitted by Jay Schupack, ‘67

As Franklin High School students, we were fortunate to experience the multicultural wonderland that filled the school's classrooms. The diversity was not only unique within the school but also mirrored the vibrant tapestry of Rainier Valley itself. Let's take a ride on the way-back machine and travel through time to explore the valley's demographic progression.

In the 1850s and 1860s, early White settlers arrived in Rainier Valley, some by ship from the East coast and others journeying along the Oregon Trail in wagons. Hailing from the Midwest, Europe, and England, settlers engaged in timber harvesting and farming. Japanese farmers also established homesteads in the Southern end of the valley during the late 1800s, while Native Americans had largely been displaced.

Rainier Valley experienced steady growth during the late 1800s, with homes being built throughout the area. Communities like Columbia City, Hillman City, York, and Brighton began to take shape with two-story buildings, dirt roads, and plank sidewalks. Grocery stores, hardware shops, and drugstores sprang up along the valley floor, which also became a railway route in 1890. The Rainier Avenue Electric Railway connected Seattle's waterfront to Columbia City, and later, Renton, with streetcar stops lining nearly every block in Rainier Valley. Schools were constructed to accommodate the growing population, starting with Columbia School in 1892, followed by Brighton Elementary and Dunlap School in 1904, with many more to come in the first two decades of the 1900s.

During this time, new settlers of various nationalities were drawn to Rainier Valley, enticed by the abundance of inexpensive land. Italians established farms and businesses in the North end of the valley, earning the area the nickname "Garlic Gulch." These farmers sold their crops to local families, restaurants, grocery stores, and distributors at the Public Market, which was partially founded by Italians. Meanwhile, several Japanese families established nurseries in the South end of Rainier Valley, and Irish, German, and other European settlers made their homes throughout the area.

Rainier Avenue was paved for car traffic in 1910, and Franklin High School was established in Mt. Baker in 1912. The Dugdale Stadium, predecessor to iconic Sick's Stadium, was built on Rainier Avenue and McClellan Street in 1913. The entire area was annexed by Seattle in 1907. Additionally, the forested Bailey Peninsula became Seward Park in 1911.

With the opening of the Lake Washington Ship Canal in 1916, connecting Lake Washington and Lake Union, the size of the lake itself decreased. Swamps dried up, and new waterfront properties became available for development, transforming the landscape of the area.

Filipino Club at Franklin, 1920. (In Quaker Times archive.)

During this time, several well-known historic establishments in Rainier Valley emerged, most of them located on or near Rainier Avenue. Our Lady of Mount Virgin Church was established in 1911, providing a place of worship. In 1914, Anton Kusak, an immigrant from Czechoslovakia, started Kusak Cut Glass. The Columbia Library, originally housed in Columbia City Hall, opened its doors in 1915, offering a hub of knowledge and learning for residents. In 1918, Constantino Oberto utilized his Italian family recipes to establish Oberto Sausage. Stewart Lumber and Hardware, serving the community's building needs, was built on Rainier Avenue about 1920. Mario Borracchini, an Italian immigrant, sold his first loaf of bread in 1922. A landmark stone gas station, Collier's Service Station, opened south of Rainier Beach in 1926, catering to the growing number of motorists in the area. The Rainier Field House, located kitty-corner from the Columbia Library, was dedicated in 1928, becoming a gathering place for community events.

Economic development experienced in the early 1900s was followed by challenging times in the late 1920s and 1930s. The Great Depression had a profound impact on almost everyone, as jobs became scarce and money became tight. Many families faced difficulties in obtaining enough food, and it was in Rainier Valley where the first breadline in Seattle was established, symbolizing the hardships faced by many.

The 1930s brought significant changes to transportation in Rainier Valley. Despite the critical role played by the Rainier Electric Railroad in the valley's development, its reputation declined due to poorly maintained equipment and unreliable schedules. The city declined to renew its franchise, leading to the train going out of business in 1937. Cars became the dominant mode of transportation. In 1940, Interstate 90 split "Garlic Gulch" and tunneled through the Mt. Baker area to reach Lake Washington and the newly constructed floating bridge connecting Seattle and the Eastside's Mercer Island.

Sick's Stadium was built in 1938 but was later demolished to make way for a Lowes Hardware Store after Seattle's first major league baseball team, the Seattle Pilots, folded following one season in 1969.

In 1940, Rainier Valley was primarily inhabited by White residents, with Italians, Germans, British, and Scandinavians making up 97 percent of the population. Asians constituted the next largest group, including Chinese, Japanese, and Filipinos. Asians and Jews resided in the Jackson Street corridor and nearby neighborhoods. The largest concentration of African Americans was found in Madison Valley, north of Rainier Valley.

The outbreak of World War II led to the forced evacuation and internment of Japanese American residents, the largest non-White group in Seattle at the time. Additionally, tens of thousands of war workers flocked to Seattle for jobs at Boeing and the shipyards, exacerbating a housing shortage. To address this, the U.S. government constructed low-cost temporary housing units in Rainier Valley, including Rainier Vista, Stadium Homes, and Holly Park. These once-stable neighborhoods became a melting pot of strangers during the war.

In 1947, two friends known as “Chubby” and “Tubby” opened a surplus store in a metal Quonset hut, serving the diverse neighborhood. Their variety store became a household name, offering an inventory as diverse as the valley's residents.

Chubby & Tubby store, ca. 1955, 3333 Rainier Avenue. (Rainier Valley Historical Society Photograph Collection)

The late 1940s witnessed ongoing housing shortages despite a boom in middle-class residential construction. Holly Park and Rainier Vista were transformed into permanent federally funded housing projects for low-income populations. Discriminatory practices such as redlining, carried out by real estate agents, banks, and restrictive covenants, kept African Americans largely confined to the Central District. Nevertheless, some people of color managed to move south into Rainier Valley. As the 1950s progressed, interracial couples found Rainier Valley more accepting than other neighborhoods. Additionally, the Seward Park and Mt. Baker areas began to attract a number of Jewish residents as they dispersed from the Central District. More Asians, who were mostly limited to the International District, began moving to Beacon Hill and the West side of Rainier Valley.

The 1950s and early 1960s in Rainier Valley were characterized by a predominantly White population. However, the population was not homogeneous, as distinct communities of Jews and Italians coexisted with Germans, Greeks, Irish, and others, each contributing their own cultural flavor to the mix. Discrimination endured, particularly for African Americans. Though some African Americans were present, most were unable to purchase homes due to continued redlining.

The Human Rights Commission, seated around a City Hall conference table, discussed means of promoting the proposed open housing law. Clockwise from left: Mrs. Victor Fleming; Y. Philip Hayasaka, (Franklin class of ’44; see Quaker Times, Spring 2022); Alfred J. Westberg, Chairman; Howard P. Pruzan; Johnny Allen (partly hidden); William B. Laney; The Rev. Lincoln P. Eng; William S. Leekenby; Elliott N. Couden (partly hidden); Rabbi Raphael H. Levine; The Rev. Edmund J. Boyle; and Mrs. Kirkby D. Walker. Members Chester W. Ramage and the Rev. Samuel B. McKinney were absent. Oct. 20, 1963. Photo credit: Richard S. Heyza/Seattle Times.

A pivotal moment in Rainier Valley’s history unfolded during the late 1960s. In 1962, then Mayor Gordon Clinton, through an advisory committee, recommended adoption of an open housing ordinance. Action on the ordinance was delayed and community members marched on City Hall. In 1964, Proposition 1 banning racial discrimination in real estate and rentals, drafted by the Human Rights Commission, was on the ballot. Seattle voters rejected it by more than a 2-1 margin. Nevertheless, the debate triggered the phenomenon known as “White flight” from Rainier Valley, Beacon Hill, and Seward Park out of fear that their neighborhoods would see an influx of Blacks.

The Beanery, a longtime lunch hangout across the street from Franklin, closed for about two months in 1968, following a boycott by Black students protesting the White ownership of the restaurant. Here, two Franklin students assist behind the counter, Barbara Simmons and Melvis Diane Williamson. The latter is the daughter of Gertrude and Nathaniel Robertson who purchased and reopened the business. Photo: Tom Barlet/Seattle PI

A year later, 1965, the U.S. Congress passed the Civil Rights Act and African Americans began moving into traditionally White neighborhoods, including Rainier Valley. In the spring of 1967, the Washington State Legislature passed a bill that prohibited discrimination by licensed real estate sales staff and brokers. A decade later the State Legislature approved further groundbreaking legislation. It prevented financial institutions from denying loans or imposing varying loan terms based on the neighborhood. These two acts made redlining illegal statewide, and opened doors for people of color wishing to purchase homes in Rainier Valley.

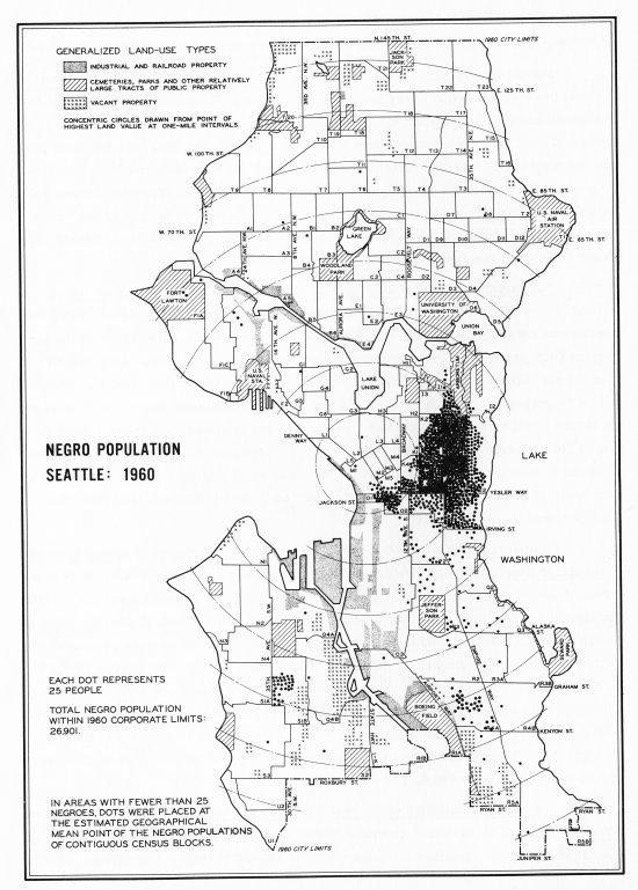

Map showing concentration of African American population in Seattle in 1960. Figure 1:6 from “Growth and Distribution of Minority Races in Seattle, Washington” by Calvin F. Schmid and Wayne W. McVey, Jr., 1964

A City of Seattle Human Rights Commission’s report, which covered 1966-1968, underscored that the neighborhood stood as an illustration of the nation’s struggle for human rights exemplified by the sit-in at the Franklin High School principal’s office in 1968. (See Quaker Times Vol. 24, Issue 2, Spring 2018.) The Human Rights Commission and key community leaders helped diffuse the tensions by opening communication, thus creating an opportunity to resolve differences among the parties. Major changes were made in Franklin’s administration and curriculum as a result.

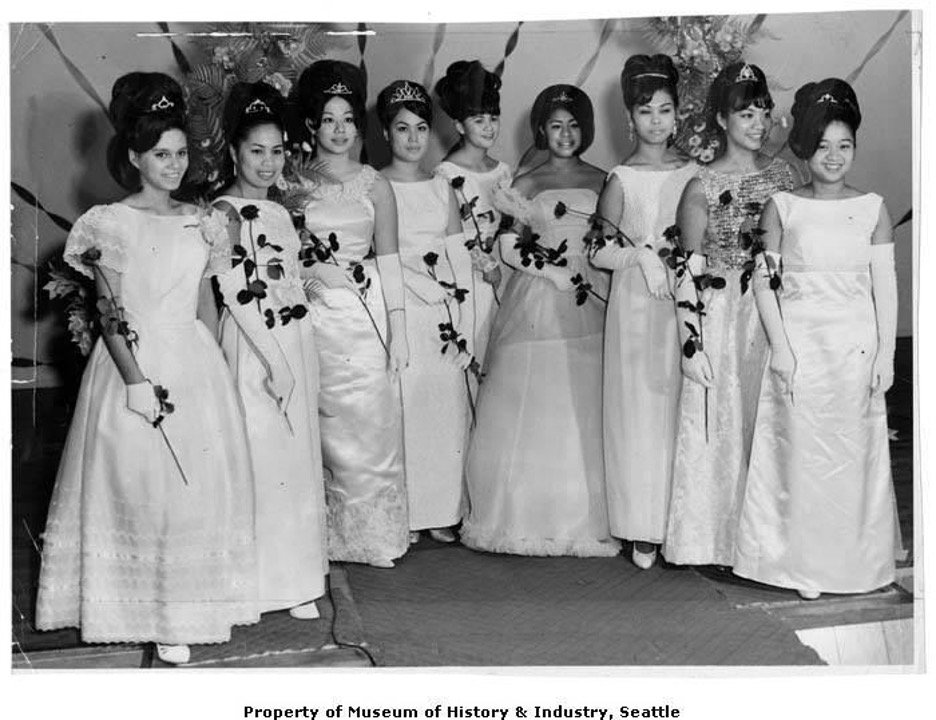

Filipino-American debutantes at Filipino Community Center, Seattle, January 11, 1967. Left to right: Linda Ramos; Bella Amor; Maria Corazon Escarte; Julie Ann Obien, (’67);Teresa Llanes; Antoinette Mamallo (’67); Zenaida Floresca; Rosalyn Antoinette Corrales; and Evelyn Patricia Zapata, (’66). Photo credit: Doug Wilson/Seattle PI.

The end of the Vietnam War in 1975 brought an influx of refugees from Indochina (Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos) to Rainier Valley, along with Hispanics from Latin America and Filipinos, adding to the multicultural fabric of the area.

Despite the economic hardships Seattle faced in the 1970s due to a Boeing bust and recession, efforts were made to revitalize Rainier Valley. SouthEast Effective Development (SEED) was founded in 1975, focusing on economic development, affordable housing, and the arts. In 1978, Columbia City received recognition as a "National Register District," leading merchants to refurbish and restore historic buildings. The U.S. Department of Housing and the Seattle Housing Authority committed to replacing the deteriorated Holly Park and Rainier Vista Housing Projects with new mixed-income housing.

The 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s witnessed waves of immigrants from East Asia and East Africa, bringing with them diverse traditions and entrepreneurial spirit. New restaurants, shops, and upgraded real estate emerged, fostering a renewed urban atmosphere. The residential housing patterns established earlier continued, as immigrants and residents from the Central District took advantage of the affordable housing in Rainier Valley. By the 1990s, the valley was more multiracial than ever, with some census tracks displaying roughly 25 percent Asian, 25 percent African American, 25 percent Latino, and 25 percent White populations. Additionally, there was a small Native American presence, along with a growing number of Ethiopians and Somalis.

The 1990s and early 2000s brought about a revitalization of neighborhoods throughout Rainier Valley. Franklin High School, which was originally planned for demolition, was saved through community efforts and remodeled, 1988-1990. The introduction of light rail brought in new people and businesses. Colman Elementary School, originally built in 1909, became a museum dedicated to African American history and culture in 2008. In that same year, the Empire bowling alley found new life as a Filipino Community Center at the opposite end of the valley.

Cambodian farmers at Rainier Vista, Seattle, 2001. (Photo: Youth in Focus Photography Program)

Rainier Valley's diversity continued to evolve, with 2023 City of Seattle data indicating a population of 36.7 percent White, 25.4 percent Asian, 14.7 percent Black, 7.1 percent Hawaiian and Pacific Islander, 6.8 percent two or more races, 5.9 percent Hispanic, 2.1 percent other, and 1.4 percent American Indian. Individuals of different European backgrounds were classified under the White category, while those with family backgrounds from Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, Japan, China, and the Philippines were counted as Asians. Seward Park retained its Jewish presence, with many families walking to synagogues on Saturdays.

The 2022-23 student body of Franklin High School reflected the multicultural makeup of Rainier Valley, with approximately 33.1 percent of Asian descent, 27.6 percent African American, 17.8 percent Latino, 13.6 percent White, 7.25 percent two or more races, and less than 0.8 percent American Indian/Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, according to the school's website and figures from the Washington Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction.

Colman School reborn as the Northwest African American Museum

From White settlers of European origin to new arrivals from the Mediterranean and Eastern Europe, to immigrants from Africa and Asia, to those migrating from the Central District and other parts of Seattle, Rainier Valley has remained a place where people from all over the world have come to achieve their dreams. As valley residents and Franklin High School students, we have been fortunate to witness, and participate in, this evolution.

References

Bryan. (2013). The Rainier Valley — a neighborhood continually in flux. Retrieved from https://nwasianweekly.com/2013/08/the-rainier-valley-a-neighborhood-continually-in-flux/

City of Seattle. (2021). Rainier Valley Neighborhood in Seattle, WA, 98144, 98118, 98178 Detailed Profile. Retrieved from https://www.city-data.com/neighborhood/Rainier-Valley-Seattle-WA.html.

Columbia City: Rainier Valley. A Short History. No Date. Neighborhood of Nations. Retrieved from https://rainiervalley.org/Cchistor.htm

Franklin High School. (2023). Retrieved from https://franklinhs.seattleschools.org/about/continuous-school-improvement-plan/

Gregory. (2020). Seattle’s Race and Segregation Story in Maps 1920-2019. University of Washington: Civil Rights & History Consortium. Retrieved from https://depts.washington.edu/labhist/maps-seattle-segregation.shtml

Johansson. (2013). Rainier Valley: One of America’s Most Diverse Neighborhoods. Retrieved from https://Seattle.Curbed.Com/2013/6/10/10234520/Rainier-Valley-One-of-Americas-Most-Diverse-Neighborhoods

OSPI. (2023). Franklin High School, Seattle School District No. 1. Washington Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction. Retrieved from https://washingtonstatereportcard.ospi.k12.wa.us/ReportCard/ViewSchoolOrDistrict/101062

Rainier Valley. (No Date). Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rainier Valley, Seattle

Rainier Valley. Arcadia Publishing, 2012

Robinson. (2017, August 16). Can the Ethiopian Community Hang on in Seattle. Https://Crosscut.Com/2017/08/Ethiopian-Community-Gentrification-Seattle-Rainier-Beach.

Seattle Human Rights Commission and Staff. (1969). City of Seattle Human Rights Commission: Report Covering August 1, 1966, to December 31, 1968. City of Seattle.

Seattle Times Staff. (n.d.). Seattle’s Rainier valley, one of America’s “Dynamic Neighborhoods." Retrieved from https://www.Seattletimes.Com/Opinion/Seattles-Rainier-Valley-One-of-Americas-Dynamic-Neighborhoods/.

Tobin, Caroline. (2004). North Rainier Valley Historic Context Statement. Retrieved from City of Seattle website: Retrieved from https://www.seattle.gov/documents/Departments/Neighborhoods/HistoricPreservation/HistoricResourcesSurvey/context-north-rainier.pdf

Wilma, David. (2001). Rainier Valley - Thumbnail History. HistoryLink.org Essay 3092. Retrieved from https://www.historylink.org/file/3092

Woodward, M. (2023, May 1). Rainier Valley Food Stories Cookbook: A Culinary Narrative of Heritage Recipes and Oral Histories. Rainier Valley Historical Society